Though the recent fighting in Georgia was triggered by events in South Ossetia, Abkhazia is another region where tensions had been brewing between the two former members of the Soviet Union.

Initially, the Abkhaz Autonomous SSR experienced very little autonomy in the 1920's and 1930's. Georgian was made the official lanaguage and Soviet authorities allowed large in-migration of Georgians, Russians, and Armenians.

Predictably, it also led to Georgian resentment. After Khrushev's economic reforms allowed for greater local control at the Union Republic level, Georgian authorities made efforts to reduce the influence of ethnic minorities. As Georgian nationalism rose, calls for greater and greater autonomy - and eventually, independence - from Moscow grew. Predictably, Georgia's growing nationalism ran into direct conflict with aspirations of the Abkhazians, who wanted to retain close relations with central Soviet authority. Abkhazian officials threatened to secede from Georgia as early as 1978. Edvard Shevardnadze, then running Soviet Georgia, staved off further moves towards Abkhazian independence from Georgia by granting further privileges to the Abkhaz people in the autonomous region.

Fighting in South Ossetia also broke out between Georgians and Ossetians before the August Putsch in 1991 that heralded the end of the USSR. The Washington Post recently reposted Michael Dobbs's reporting on the first round of fighting between South Ossetia and Georgia in 1991:

But this is also a war in which notions of right and wrong, oppressors and oppressed, have become impossibly tangled with centuries-old ethnic disputes. There seems little doubt that the Kremlin has been using minority grievances as a means of bringing pressure to bear on rebellious Soviet republics, such as Georgia. At the same time, Georgia's own treatment of its ethnic minorities has drawn sharp criticism from Western human-rights activists. During a three-week occupation of Tskhinvali in January, Georgian militia units ransacked the Ossetian national theater. The plaster statue of Ossetia's national poet, Kosta Khetagurov, was decapitated. Monuments to Ossetians who fought with Soviet troops in World War II were smashed to pieces and thrown into the river.********Georgian mistrust of the Ossetians is deeply rooted. For [Georgian nationalist leader] Gamsakhurdia, along with most of his compatriots, the present conflict is a replay of what happened in 1920-22, when a fledgling Georgian state was crushed by the Red Army. The Ossetians sided with the Bolsheviks against the Menshevik government in Tbilisi during the Soviet civil war. In return, the Georgians say, the Ossetians were rewarded with an "autonomous region" within Georgia in addition to the autonomous republic of North Ossetia in Russia.

The New York Times today published an account of the difficulties endured by South Ossetians at Georgia's hands beginning in the late 1980's.

Abkhazia and South Ossetia were not unique. The decision to place the Armenian dominated Nagorno-Karabakh under the jurisdiction of Azerbaijan had a similar effect -- and similarly, led to armed conflict when the Soviet Union ceased to exert central authority. With the stroke of a pen, Stalin could redraw the lines of the internal borders of the Soviet Union. For example, according to a recent article in Izvestiya, Stalin almost used his line-drawing power in 1925 to place North Ossetia - currently part of Russia - into the Georgian Republic. Similarly, Khruschev gave Crimea - likely the site of coming conflict - to Ukraine in 1954.

In short, the borders that McCain - at least by his bellicose rhetoric - would have the U.S. military fight to protect are borders that are an artifact of an intentional policy, originated by Stalin, to help Moscow keep control over its vast empire.

Where do you draw the line on the use of force?

Georgia and its allies in the U.S. - including McCain with his Yosemite-Sam-bluster - have repeatedly thrown around "territorial integrity" and "disproportionate force" in making the case against Russia's actions in Georgia.Wrapping Russia's knuckles with these phrases has not caused the Russians to flinch. Whether it is a fair analogy or not, Russian officials point to the west's decision to wrest Kosovo from Serbia as precedent for ignoring territorial integrity when an ethnic minority enclave wants to secede from its erstwhile state. And when it comes to disproportionate force, the United States led NATO military action to "liberate" Kosovo resulted in 38,000 sorties, many aimed directly at Serbia's civilian infrastructure (including the Zastava Automobile plant, -pictured below - source of the once beloved Yugo), doing far more extensive damage in Serbia than did the Russian military in Georgia.

I recognize that Russia's claims of "genocide" by Georgians in South Ossetia are most probably bogus; the Kosovar Albanians received more despicable treatment from Slobodan Milošević's Serb army than anything the South Ossetians got from Georgia. Christopher Hitchens has explained many reasons why Russia's attempt to rely on Kosovo as precedent for recognizing South Ossetian or Abkhazian independence is not justified. But these recent, European ethnic conflicts are not as simple as they seem -- Hitchens, for example, fails to recognize that the worst atrocities in Kosovo did not begin until the NATO bombing campaign commenced and that the KLA had themselves committed a number of atrocities against Serb civilians living in the province. I am not suggesting that responsible policy makers in Europe or the U.S. should simply shrug off confronting such ethnic conflicts -- but it is hard to take sides without collaborating with very bad actors on one side or the other.

The former British ambassador to Yugoslavia, Sir Ivor Roberts, states the problem we have created for ourselves: "when the United States and Britain backed the independence of Kosovo without UN approval, they paved the way for Russia's 'defense' of South Ossetia, and for the current Western humiliation.

"What is sauce for the Kosovo goose is sauce for the South Ossetian gander."I suspect that Russia goaded Georgia to launch its ill fated attack in South Ossetia, thus providing pretext for its military intervention. It is fair to label Russia's military actions in Georgia as disproportionate when compared to the Georgian incursion into South Ossetia. But for the United States to preach this sermon sounds to me like Hugh Hefner lecturing on the virtues of celibacy.

Where do you draw the line on hyperbole?

Putin has said that the disbanding of the Soviet Union was the "greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the [twentieth] century." Considering the vast human suffering caused by Soviet authorities, one might be more inclined to think that the formation of the Soviet Union was the greatest catastrophe of the last century. Putin went on to explain that the "catastrophe" became a "tragedy" for ethnic Russians who ended outside of Russia after the final break-up. Which brings us back to nationalism in the former Soviet Union.

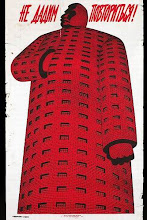

Putin has said that the disbanding of the Soviet Union was the "greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the [twentieth] century." Considering the vast human suffering caused by Soviet authorities, one might be more inclined to think that the formation of the Soviet Union was the greatest catastrophe of the last century. Putin went on to explain that the "catastrophe" became a "tragedy" for ethnic Russians who ended outside of Russia after the final break-up. Which brings us back to nationalism in the former Soviet Union.Russian nationalism is on the rise. And with it, hope of Russia establishing an open society dwindles.

Putin has skillfully exploited Russians' resentment at losing so much in such a short amount of time. Putin's emergent imperial nationalism follows Boris Yeltsin's brand of nationalism, which was premised on Russia withdrawing from the Soviet Union in order to focus on reconstructing itself. Despite the cultural and linguistic dominance of Russian in the Soviet Union, Russia did not reap economic benefit from its membership in the USSR; under the centrally planned economy, wealth flowed out of Russia and into development projects in the far corners of the Soviet Union. Though Russia has a long way to go to build its own, modern infrastructure, Putin's brand of nationalism includes using Russia's military muscle to exert its influence in its so-called "near abroad." There has yet to be a coherent United States response to this shift.

Putin has skillfully exploited Russians' resentment at losing so much in such a short amount of time. Putin's emergent imperial nationalism follows Boris Yeltsin's brand of nationalism, which was premised on Russia withdrawing from the Soviet Union in order to focus on reconstructing itself. Despite the cultural and linguistic dominance of Russian in the Soviet Union, Russia did not reap economic benefit from its membership in the USSR; under the centrally planned economy, wealth flowed out of Russia and into development projects in the far corners of the Soviet Union. Though Russia has a long way to go to build its own, modern infrastructure, Putin's brand of nationalism includes using Russia's military muscle to exert its influence in its so-called "near abroad." There has yet to be a coherent United States response to this shift.What I do not understand is why the U.S. is assisting Putin, why America is fueling the flames of this resurgent nationalism. What vital U.S. interests are served by having Georgia or Ukraine join NATO? Why did the U.S. continue George Kennan's policy of containment against Russia even after the wall came down and Russia made efforts to adopt a western, capitalist system? The U.S. appears to be pursuing a dizzying array of shifting priorities in the region: securing nuclear weapons material; promoting democracy; ignoring democracy - by engaging with despotic and/or undemocratic regimes like those in Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan to negotiate gas or oil pipelines bypassing Russia and Iran; and relying on Russia's assistance to negotiate with Iran or North Korea. What will be next?

The U.S. will probably have little role in redrawing the map of Georgia, but it should put some thought into whether it is helping or hurting the cause of promoting civil society in Russia. Nader Mousavizadeh, former special assistant to the UN Secretary- General Kofi Annan, has written a thoughtful summary of the choices the U.S. faces in the Times of London:

Which brings us to the real lesson of the Georgian debacle: Tbilisi's freedom to challenge Russia had already been traded away by its Western allies - whether they realised it or not. When Kosovo declared independence in February, a senior European official remarked that the West would pay a price for its decision to offer recognition in the face of fierce Russian opposition.Instead, the U.S. government continues to draw rhetorical lines in the sand with regard to "acceptable" Russian actions -- apparently oblivious to the reality that America cannot have it all. As Putin and Medvedev understand, we lack the resources, will and stomach to put our money or military where our mouth is when Russia crosses those lines. Though the U.S. does not want to concede that Russia is playing in its neighborhood sandbox, calling Russia a bully from a balcony down the street is not likely going to make any difference to other kids on Russia's block.*****

The lesson is not that the West was wrong to recognise Kosovo or that Nato was right to delay Georgia's membership. Rather, it is to suggest that we increasingly live in a world of choices. We may be able to enjoy the satisfaction of supporting the Kosovans or encouraging the Georgians, but we may not be able to do so without paying a price in another arena.

No comments:

Post a Comment